Dynamic Human-AI Interaction

Published:

As a PhD student watching new arXiv papers pop up every day, I keep asking myself: what are the topics we should work on, especially when so many benchmarks can be pushed by just scaling data and models? After a small mid-PhD crisis, I’ve (tentatively) landed on one thing I personally care a lot about: dynamic human-AI interaction.

What Do You Mean… And Why?

There are lots of directions in application-level work right now: better training recipes, “comprehensive” benchmarks (btw I still kinda hate this word haha), new tasks… all cool and important. But in late 2025, I’m honestly not that surprised when a new model solves yet another single, well-defined task with enough scale. What feels more interesting and foundational to me is how people actually interact with these systems: if we don’t know what the interaction looks like, what are you really trying to model? And which evaluations are actually valuable?

So, what do I mean by dynamic human-AI interaction, and what’s missing today?

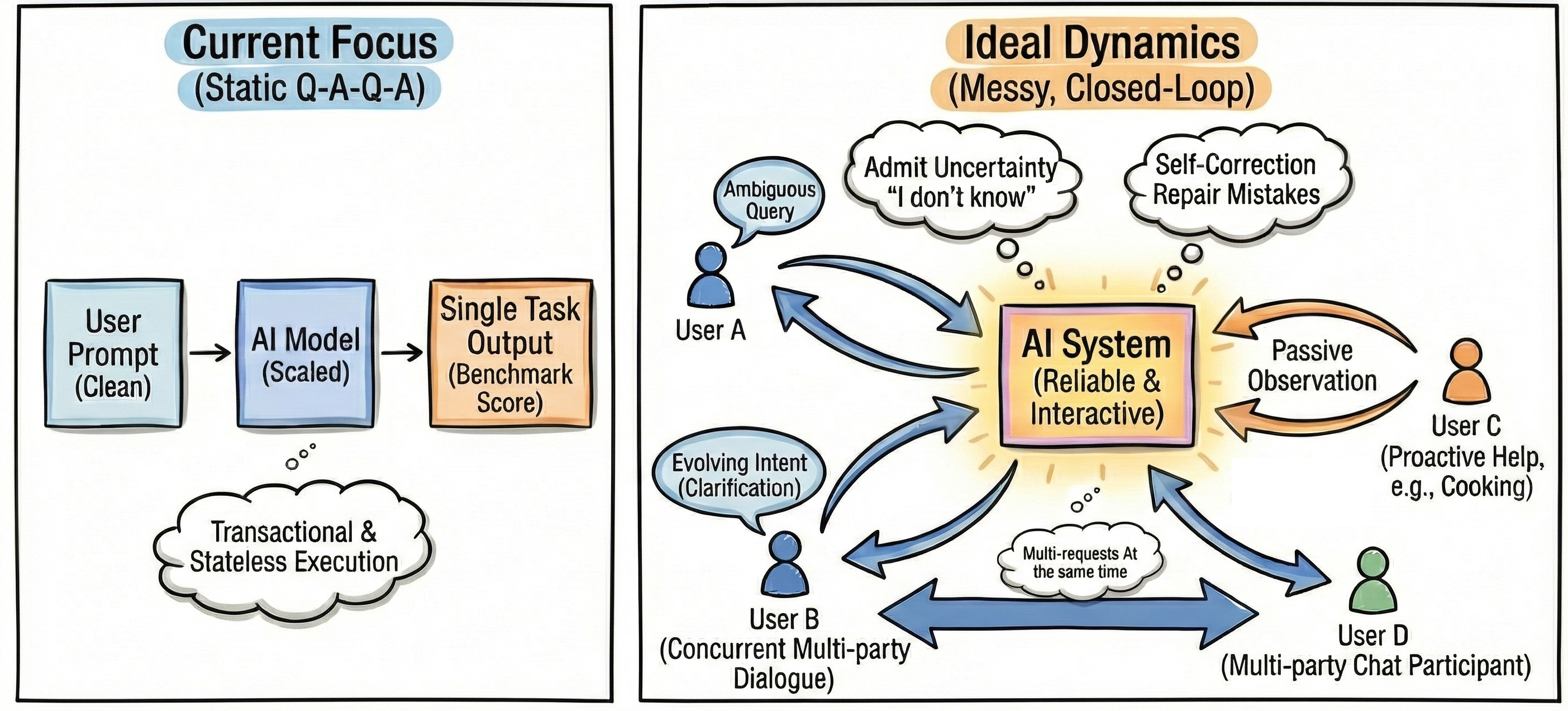

As shown in the figure above, we currently mostly think about models answering clean, well-defined prompts, turn by turn. However, that’s just the tip of the iceberg. In reality, users ask ambiguous or downright silly questions, change their minds halfway through, or jump around in messy multi-party chats. Sometimes we want to do nothing and still have the model help us by saying the right thing at the right time (like when you’re cooking and the pan is almost on fire LOL).

Also, no matter how weird the input is, we still expect models to behave reliably over time. To clarify, that doesn’t mean “never make mistakes” (that’s impossible); as model generally performs well nowadays, it means that in a closed-loop setting, when the model drifts off track, it should notice, say so, and help steer things back. A reliable model can admit “I don’t know,” surface uncertainty, and try to repair its own mistakes instead of silently hallucinating a confident answer.

In the rest of this post, I’m gonna point out some key topics I personally feel important into and then end with a small final remark.

The Full Spectrum of Interaction

We humans are complicated, imperfect, and a little chaotic ;-). From 2022–2025, models have gotten very good at answering nicely written prompts. But most systems still assume a clean Q-A-Q-A loop: I ask a question (Q), the model answers (A), I ask again (Q), it answers again (A). That’s great for benchmarks and demos; it’s not how people actually behave.

As we discussed briefly above, once you stop thinking in terms of neat, turn-based Q-A-Q-A and start thinking in terms of an ongoing, closed-loop interaction, a lot of “odd cases” suddenly look like core behaviors. The interesting questions become: How should a model react when the premise is off/vague, what happens when we cut into model’s reaction mid-stream, and when should it be the one to speak up first? In the rest of this section, I’ll group these into three regimes: imperfect, changing, and dangerous/collaborative contexts.

1. Reactive to Imperfect Contexts.

In real-world usage, prompts often rely on imperfect contexts: users aren’t “benchmarking” models but just want help. A user might ask to “find the cat in the bedroom” when the cat is actually in the kitchen, or a blind user might ask about a scene they cannot see.

A purely obedient system will hallucinate an answer to satisfy the prompt. A reactive system, however, should push back: flagging mismatches, asking for clarification, or offering alternatives. In SESAME, we study this via false-premise segmentation: how vision models respond when a request conflicts with the scene. While datasets like AbstentionBench and SORRY-Bench for false-premise scenarios are emerging, the challenge of handling vague goals, missing contexts, or messy multi-round negotiations/context-providing still feels wide open. Oh and btw, throughout that process, the model has to resist being “talked into” violating safeguards!

2. Flexible to Changing Contexts.

Models must also adapt to ever-changing contexts, especially in long-horizon tasks. Different from conventional frozen-world evaluate protocol, the real world constantly interrupts us with new requirements or environmental states (e.g., sudden rain). If we cut a model mid-thought or mid-action to inject new information, does it gracefully re-plan?

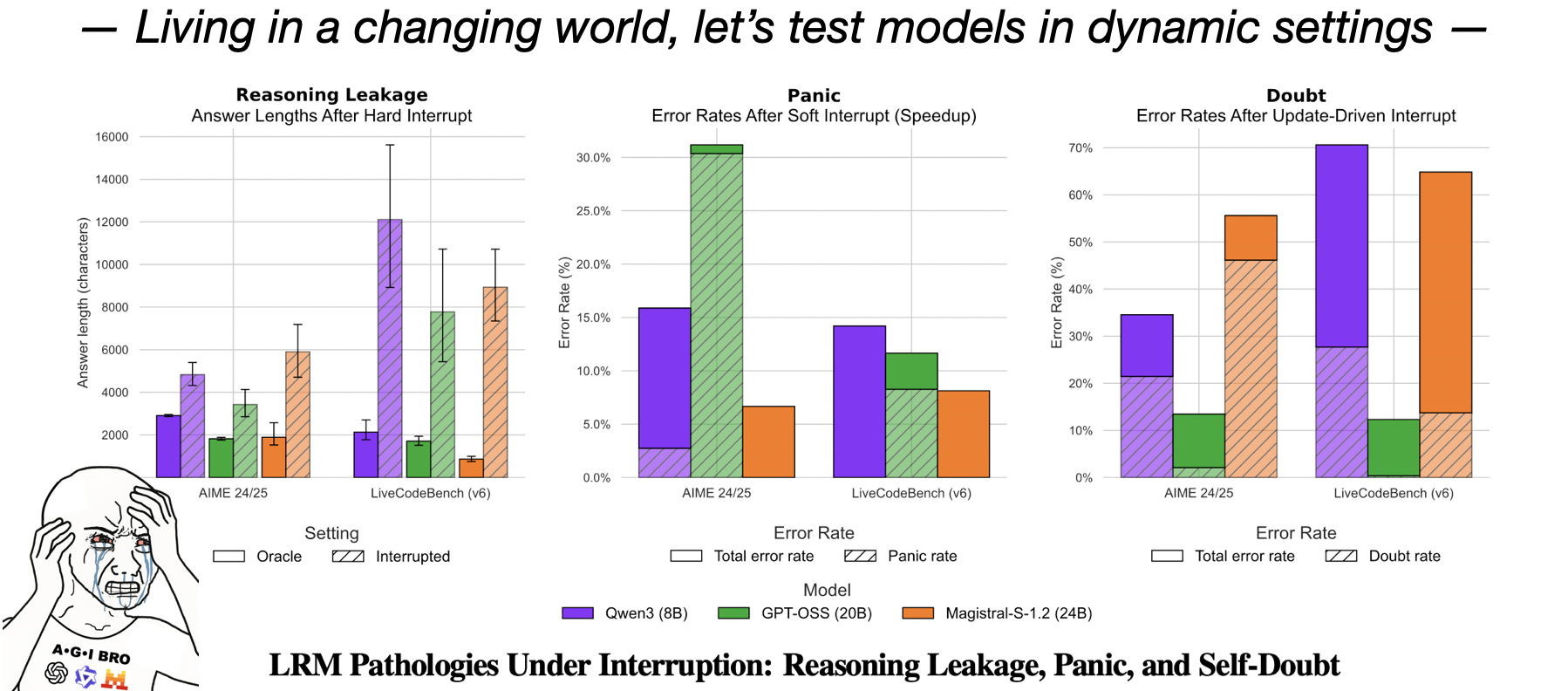

In our interruptible-LRM work, we tested this by interrupting models during math and coding tasks. The results show that current models suffer from “reasoning leakage”, “panic”, and “self-doubt”. Robustness to changing context is clearly a missing core capability; to cooperate effectively with humans and operate in environments full of objects and unexpected events, models must treat interruptions as a standard feature of the world, not an edge case. Following our work, one recent paper also applies the changing-context idea to agentic scenarios!

3. Proactive in Dangerous, Collaborative Contexts

So far I’ve talked about cases where the human initiates the next move. But the Q–A–Q–A view also quietly assumes something else: that the model should always wait for a user query before doing anything. In high-stakes or collaborative (teaching) situations, like coding with risky commands, teaching people to cook, or playing video games together, this assumption breaks down. We need proactive assistants that step in before things go wrong.

Such a system would track shared state and gently interrupt when it detects danger: “Hey, this command will delete everything,” or “Your trading strategy fails under these conditions.” Here the model proactively initiates the “turn” based on the context, not just explicit queries. That’s a very different interaction contract than “wait for user input, then answer.” While some proactive benchmarks and datasets have been proposed (e.g., ProactiveVideoQA, Proactive Assistant Dialogue), I believe it’s still in an early stage.

These three cases above are just a few slices of what I mean by dynamic human-AI interaction. Some of them I’ve already worked on (false-premise perception, interruptible reasoning), and others I’m still figuring out how to tackle. We can also extend this to multi-user or multi-agent settings, where we have to ask who’s allowed to interrupt whom, how to resolve conflicting goals, and how to keep things stable instead of chaotic. But even in the simplest setting, with just one human and one model, there’s already a huge space to explore beyond the classic Q–A–Q–A picture.

Towards Reliable AI Systems

We want models to be reliably helpful over time, not just occasionally brilliant. As we said, that doesn’t mean zero errors; it means that when they drift off track, they should notice, say so, and try to repair themselves after they messed up. To me, that’s what closed-loop self-correction is about: instead of a one-shot input→output pipeline, the model lives in a loop: checking its own work, revising themselves (including the content or their own configurations) when needed, and communicating uncertainty!

Early in my PhD, I explored this idea in an image generation domain (my only diffusion project) rather than the LVLM setting I mostly work on now. In our work on self-correcting LLM-controlled diffusion models, the approach was modular and simple: first generate an image, then run separate modules to inspect, critique, and refine it. In hindsight, it’s a pretty straightforward design, but I see it as my first concrete step toward closed-loop behavior. That project made me realize how powerful it can be when a system is allowed to look at its own output and say, “Wait, this isn’t quite right. Let me try again.”

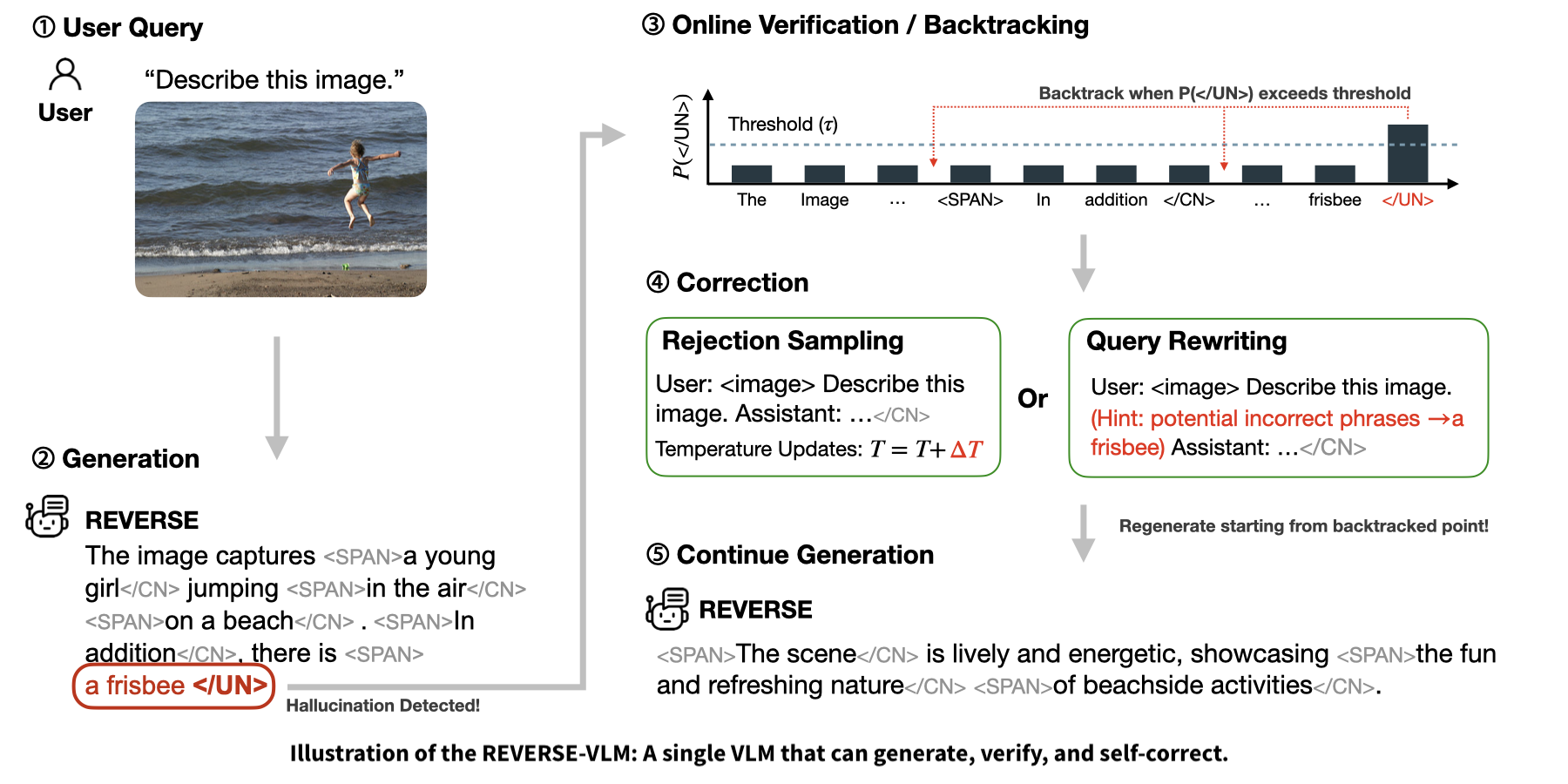

More recently, in our REVERSE work on LVLM, we pushed this idea further and closer to how humans actually reason. Instead of stitching together multiple external components, we turn a single model into a generate-then-verify system: the model produces an answer, then re-reads its own reasoning and output, flags possible hallucinations, and selectively revises. Crucially, this process is controllable: we can tune how aggressively the model verifies itself, how much cost we’re willing to pay for extra checks, and how conservative we want it to be in safety-critical settings. It’s like giving the system a “caution slider” instead of a fixed behavior.

Both of these projects are small pieces of a bigger picture: building AI systems that don’t just answer, but monitor, question, and correct themselves in a closed loop. Looking forward, I see the generate-but-verify paradigm as a key part of that future: we should teach models to faithfully express their uncertainty under a given configuration, and then adapt their settings or behavior to self-correct their own outputs. Paired with the interaction cases above, this opens up a lot of opportunities. For instance, in vision–language–action (VLA) systems, it’s not enough to propose a sequence of actions once. After acting, the agent should continuously verify the environment, detect mismatches between expectation and reality, and tweak its high-level plan when required.

Final Remarks

Okay this post ended up much longer than I planned, but the main point is simple. If we take the full spectrum of human-AI interaction seriously and think in terms of closed-loop, messy, real-world dynamics rather than one-shot prompts, we might start to see a lot of interesting questions and failure modes that current work mostly ignores.

I know some of what I am doing can look “incremental” or “too application-y” next to giant scaling papers or shiny new architectures, and I think that criticism is fair. But if any of this resonates, I’d love to talk. Catch me at a conference, send a DM, or say hi if you see me wandering around Berkeley with a laptop and too much tea or boba. I’m always down to trade rants, weird failure cases, and ideas for what truly dynamic human–AI interaction could look like next.

Final Note: Thanks to all of my collaborators, advisors, and peers I met throughout these time!